The Feed 2025-02-21

AI Generated Podcast

https://open.spotify.com/episode/4Gv7u1K1qUUPg4WVy8DyGS?si=UiJt7PdHSVi8E0sWNZ3XMA

Summarized Sources

- An inside look at NSA (Equation Group) TTPs from China’s lense: This blog post aggregates and shares Chinese cybersecurity entities’ reports on NSA’s cyber operations (APT-C-40), focusing on the alleged attack on China’s Northwestern Polytechnical University, to identify new detection or offensive techniques.

Original link: https://www.inversecos.com/2025/02/an-inside-look-at-nsa-equation-group.html

- CopyObjection: Fending off ransomware in AWS: This article discusses a ransomware technique abusing server-side encryption with customer-managed keys (SSE-C) in AWS S3 and proposes an automated detection and response pipeline using CloudWatch and Lambda to mitigate the threat.

Original link: https://redcanary.com/blog/incident-response/aws-ransomware/

- Earth Preta Mixes Legitimate and Malicious Components to Sidestep Detection: This article examines how the APT group Earth Preta uses MAVInject and Setup Factory to deploy payloads, maintain control over compromised systems, and evade detection by mixing legitimate executables with malicious components.

Original link: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/25/b/earth-preta-mixes-legitimate-and-malicious-components-to-sidestep-detection.html

- Invisible obfuscation technique used in PAC attack: This post describes a new JavaScript obfuscation technique using Hangul filler characters observed in a phishing attack targeting a major American political action committee, providing code snippets for defenders.

Original link: https://blogs.juniper.net/en-us/threat-research/invisible-obfuscation-technique-used-in-pac-attack

-

**whoAMI: A cloud image name confusion attack Datadog Security Labs**: This article describes a vulnerability in how AWS AMI IDs are retrieved that allows attackers to gain code execution by publishing AMIs with specially crafted names, and it offers methods to detect and prevent such attacks, including AWS’s new Allowed AMIs feature and the whoAMI-scanner tool.

Original link: https://securitylabs.datadoghq.com/articles/whoami-a-cloud-image-name-confusion-attack/

An inside look at NSA (Equation Group) TTPs from China’s lense

Summary

This blog post analyzes Chinese cybersecurity entities’ reports on the NSA’s alleged cyber operations, specifically the attack on China’s Northwestern Polytechnical University. The reports, stemming from Qihoo 360, Pangu Lab, and the National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center (CVERC), detail the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) allegedly used by the NSA, referred to as APT-C-40, during the 2022 breach. The analysis covers pre-attack preparation, initial access, persistence, lateral movement, data exfiltration, and evasion techniques. The report highlights the use of zero-days, MiTM attacks, spear phishing, and various tools for maintaining access and stealing data. It also contrasts Western and Chinese incident response methodologies, noting China’s extensive use of big data analysis in tracking attacker activity.

Technical Details

The alleged attack on Northwestern Polytechnical University involved a multi-stage process:

The alleged attack on Northwestern Polytechnical University involved a multi-stage process:

- Pre-Attack Preparation: The NSA utilized zero-day exploits to compromise servers with SunOS in countries neighboring China. This was done to establish jump servers for the main attack. The SHAVER tool was used to exploit SunOS servers with RPC services enabled. 54 jump servers and 5 proxy servers across 17 countries were used, with 70% located in China’s neighboring countries.

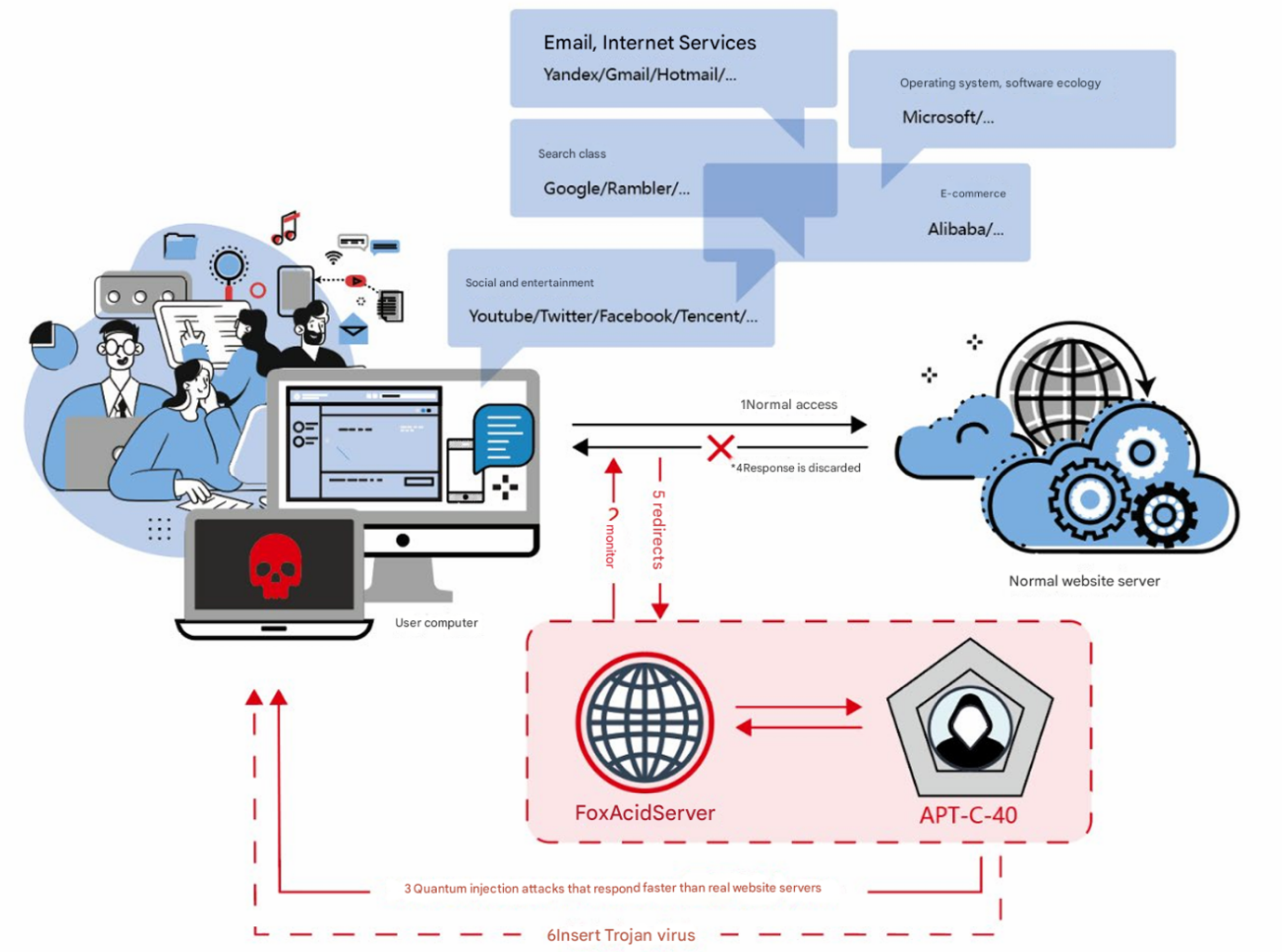

- Initial Access: The attackers used spear-phishing emails containing malware and MiTM attacks. Emails referencing “scientific research review” were sent to university staff and students. The FOXACID platform, a 0-day exploit delivery system, was employed to inject malware into users’ browsers when accessing websites. Compromised external servers used the ISLAND tool for manual exploitation of Solaris systems. SECONDDATE, an espionage software, was installed on network devices to monitor/tamper with traffic and redirect users to the FOXACID platform.

- Persistence and Lateral Movement: After gaining initial access, the attackers focused on maintaining persistence and moving laterally within the network. SECONDDATE was used as a backdoor on network edge devices to hijack traffic. NOPEN, a remote-controlled malware, allowed for file execution, process management, and privilege escalation. FLAME SPRAY, a Windows-based remote-controlled malware, was used with the FOXACID platform. CUNNING HERETICS, a lightweight implant, established encrypted communication channels. STOIC SURGEON, a stealthy backdoor, targeted Linux, Solaris, JunOS, and FreeBSD systems.

- Lateral Movement Techniques: The attackers targeted edge network devices and used legitimate credentials to access firewall appliances. They also compromised software update mechanisms to distribute malware. The DRINKING TEA tool was used to sniff SSH, Telnet, and Rlogin passwords.

- Data Exfiltration: Classified research data, network infrastructure details, and sensitive documents were stolen. Tools such as OPERATION BEHIND ENEMY LINES, School of Magic, Clown Food, and Cursed Fire were used to extract sensitive files. Data was routed through 54 jump servers and proxy nodes in 17 countries.

- Evasion and Anti-Forensic Measures: The attackers used anti-forensic techniques to minimize detection. TOAST BREAD, a log manipulation tool, erased evidence of unauthorized access. All tools used encryption for undetectable communication.

The investigation and forensics uncovered that the attackers:

- Primarily operated during 9am – 16pm EST (US working hours)

- Did not conduct attacks on Saturdays, Sundays, Memorial Day, Independence Day, or Christmas

- Used American English, English OS and applications, and an American keyboard

- Inadvertently exposed the working directory and filename of their internet terminal due to an error while running a Pyscript tool In contrast, Western methodologies typically focus on constructing a super timeline of an attack, detailing events in chronological order. Timelines are compiled, indicators of compromise (IoCs) are documented, and reports are handed off to intelligence teams, often accompanied by a verbal debrief. Large-scale data analysis using AI across multiple cases—or even on a single case—is not a standard practice in the West.

Countries

- Jump servers and proxy nodes located in Japan, South Korea, Sweden, Poland, Ukraine, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Netherlands, Denmark, Italy, Mexico, Germany, Finland, Spain, Qatar, and UAE

Industries

- Aerospace and defense (Northwestern Polytechnical University)

- Educational institutions and commercial organizations (used as jump servers)

- Telecom operators

Recommendations

- Monitor and secure edge devices, IoT devices, and network appliances.

- Implement robust logging and monitoring on network devices.

- Enhance incident response methodologies with big data analysis to identify patterns in attacker activity.

- Be aware of the potential for attacks operating in-memory without writing files to disk.

Hunting methods

- Edge Device Monitoring: Implement specialized monitoring for edge devices, IoT devices, and network appliances, focusing on unusual traffic patterns and unauthorized access attempts.

- Network Traffic Analysis: Inspect network traffic for patterns indicative of MiTM attacks and redirection to unusual or known malicious servers.

- Credential Monitoring: Monitor for the use of stolen credentials, especially on network devices and telecom operator systems.

- Log Analysis: Search for evidence of log manipulation using tools like TOAST BREAD.

IOC

NSA IPs (Purchased through cover companies):

- 209.59.36.xx\

- 69.165.54.xx\

- 207.195.240.xx\

- 209.118.143.xx

Weapon Platform IPs (C2 Servers):

- 192.242.xx.xx (Colombia)\

- 81.31.xx.xx (Czech Republic)\

- 80.77.xx.xx (Egypt)\

- 83.98.xx.xx (Netherlands)\

- 82.103.xx.xx (Denmark)

IPs Used to Launch Attacks:

- 211.119.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 211.119.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 211.233.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 143.248.xx.xx (Korea - Daejeon Institute of Science and Technology)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 211.233.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Korea - Korea National Open University)\

- 211.233.xx.xx (Korea - KT Telecom)\

- 89.96.xx.xx (Italy - Milan)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan - Tokyo)\

- 147.32.xx.xx (Czech Republic - Brno)\

- 132.248.xx.xx (Mexico - UNAM)\

- 195.162.xx.xx (Sweden)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan - Tokyo)\

- 210.228.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 211.233.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 212.187.xx.xx (Germany - Nuremberg)\

- 222.187.xx.xx (Germany - Bremen)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 91.217.xx.xx (Finland)\

- 211.233.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 84.88.xx.xx (Spain - Barcelona)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan - Kyoto University)\

- 132.248.xx.xx (Mexico)\

- 148.208.xx.xx (Mexico)\

- 192.162.xx.xx (Italy)\

- 211.233.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 218.232.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 148.208.xx.xx (Mexico)\

- 61.115.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 130.241.xx.xx (Sweden)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (India)\

- 210.143.xx.xx (Japan)\

- 202.30.xx.xx (Australia)\

- 220.66.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 222.122.xx.xx (Korea)\

- 141.57.xx.xx (Germany - Leipzig Institute of Economics and Culture)\

- 212.109.xx.xx (Poland)\

- 210.135.xx.xx (Japan - Tokyo)\

- 148.208.xx.xx (Mexico)\

- 82.148.xx.xx (Qatar)\

- 46.29.xx.xx (UAE)

- 143.248.xx.xx (Korea - Daejeon Institute of Science and Technology)

SecondDate CnC

- MD5: 485a83b9175b50df214519d875b2ec93\

- SHA-1: 0a7830ff10a02c80dee8ddf1ceb13076d12b7d83\

- SHA-256: d799ab9b616be179f24dbe8af6ff76ff9e56874f298dab9096854ea228fc0aeb

Original link: https://www.inversecos.com/2025/02/an-inside-look-at-nsa-equation-group.html

CopyObjection: Fending off ransomware in AWS

Summary

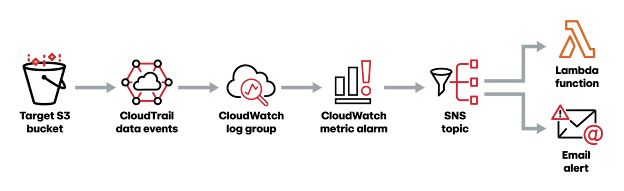

This article discusses how ransomware attacks are targeting cloud resources, specifically focusing on the abuse of server-side encryption with customer-managed keys (SSE-C) in AWS S3 buckets. Adversaries can copy and encrypt S3 objects, preventing victims from recovering the encryption keys. The author details an experiment using CloudWatch for detection and Lambda functions for automated remediation. The experiment aimed to measure the response time from initial CopyObject command to the prevention of further encryption. The results showed that while the automated response (disabling access keys or applying deny-all policies) was immediate once triggered, the delivery of CloudTrail logs to CloudWatch took approximately 6 minutes. The article emphasizes the importance of auto-remediation and proactive measures to minimize dwell time and potential data encryption.

Technical Details

The article outlines a method for detecting and responding to ransomware attacks in AWS environments that leverage the abuse of SSE-C:

The article outlines a method for detecting and responding to ransomware attacks in AWS environments that leverage the abuse of SSE-C:

- Abuse of SSE-C: Adversaries copy S3 objects in place and encrypt them using server-side encryption with customer-managed keys (SSE-C). Because AWS does not store these keys, the victim cannot recover the data.

- Testing Environment: The testing environment included an IAM user with AmazonS3Full access, configured with a long-term access key. The S3 bucket contained files ranging from 500 KB to 2 MB to emulate typical document storage.

- Ransomware Execution: The author mimicked an adversary by performing copy in place operations to bulk-encrypt files in the S3 bucket.

- Detection Pipeline: The detection pipeline used CloudWatch to monitor and trigger alerts. CloudTrail events from the target S3 bucket were sent to a CloudWatch log group. A metric alarm was set to trigger upon detecting 10 concurrent CopyObject calls within a 1-minute period.

- Automated Remediation: Upon alarm trigger, a Lambda function was executed. Two versions of the Lambda function were tested:

- Disabling the IAM user’s access key

- Applying a deny-all policy to the test user

- Response Time: The primary delay in response time was the delivery of CloudTrail logs to CloudWatch, averaging around 6 minutes, consistent with AWS documentation. Once the alarm was triggered, the automated response (disabling access key or applying deny-all policy) was immediate.

The Lambda code in the source uses the boto3 library to interact with AWS IAM. It disables the user’s access key or attaches a policy to deny all actions. The code includes error handling to catch exceptions and log messages for debugging.

Recommendations

- Implement automated remediation to cut off user access immediately upon detection of suspicious activity.

- Tailor automated responses to the specific environment and business needs.

- Develop behavioral indicators of pre-encryption behavior to reduce dwell times.

- Follow AWS’s security practices to block unauthorized access to SSE-C if it is not being used.

- Consider implementing a resource control policy (RCP) to disable SSE-C across the account.

Hunting methods

- Monitor CloudTrail logs for concurrent CopyObject calls within a short timeframe.

- Analyze CloudWatch metrics for spikes in CopyObject activity.

- Investigate unusual IAM user activity, especially related to S3 object encryption.

Original link: https://redcanary.com/blog/incident-response/aws-ransomware/

Earth Preta Mixes Legitimate and Malicious Components to Sidestep Detection

Summary

This article details a new technique used by the Earth Preta APT group (also known as Mustang Panda), which involves leveraging the Microsoft Application Virtualization Injector (MAVInject.exe) to inject malicious payloads into waitfor.exe. This process occurs when an ESET antivirus application is detected. Earth Preta also utilizes Setup Factory, an installer builder for Windows, to drop and execute payloads for persistence and to evade detection. The attack involves dropping a combination of legitimate and malicious files, including a decoy PDF to distract the victim. The malware, a variant of the TONESHELL backdoor, is sideloaded with a legitimate Electronic Arts application and communicates with a command-and-control server for data exfiltration. The group has been known to target the Asia-Pacific region, with recent campaigns targeting Taiwan, Vietnam, and Malaysia, among others. They typically use spear-phishing techniques and have targeted government entities, with over 200 victims since 2022. Trend Micro’s Threat Hunting team discovered this technique.

Technical Details

The Earth Preta attack chain involves the following steps:

- Initial Infection: The attack starts with a malicious file,

IRSetup.exe, which drops multiple files into theProgramData/sessiondirectory. These files include legitimate executables, malicious components, and a decoy PDF. - Decoy Execution: A decoy PDF is executed, likely to distract the victim while the malicious payload is deployed in the background. This PDF is designed to target Thailand-based users.

- DLL Sideloading: The dropper malware executes

OriginLegacyCLI.exe, a legitimate Electronic Arts (EA) application, to sideloadEACore.dll, which is a modified variant of the TONESHELL backdoor. - ESET Detection Check:

EACore.dllchecks ifekrn.exeoregui.exe(both associated with ESET antivirus applications) are running. - Payload Injection:

- If ESET is detected,

EACore.dllis registered usingregsvr32.exeto execute theDLLRegisterServerfunction, which then executeswaitfor.exe.MAVInject.exeis used to inject malicious code intowaitfor.exe. The command used isMavinject.exe <Target PID> /INJECTRUNNING <Malicious DLL>. - If ESET is not detected, the malware implements an exception handler and directly injects code into

waitfor.exeusingWriteProcessMemoryandCreateRemoteThreadExAPIs.

- If ESET is detected,

- C&C Communication: The malware decrypts shellcode stored in the

.datasection and communicates with the command-and-control (C&C) server atwww[.]militarytc[.]com:443. It generates a random identifier, gathers the computer name, and sends this information to the C&C server. The generated victim ID is stored tocurrent_directory\CompressShadersfor persistence. - Data Exfiltration: The TONESHELL backdoor communicates with the C&C server to exfiltrate data.

The malware uses the ws2_32.send API call to communicate with the C&C server. The C&C protocol is similar to previous variants but includes minor changes in the handshake packet and command codes. The malware supports command codes 4 through 19 and has capabilities such as reverse shell, file deletion, and file movement.

Countries

- Asia-Pacific region (Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia)

- Thailand (decoy PDF targets Thailand-based users)

Industries

- Government entities

- All industries vulnerable

Recommendations

- Enhance monitoring capabilities to identify unusual activities in legitimate processes and executable files.

- Organizations should be vigilant about monitoring for the execution of legitimate applications like Setup Factory and OriginLegacyCLI.exe to detect the attack.

- Leverage Threat Insights to stay ahead of cyber threats and prepare for emerging threats.

Hunting methods

- Use Trend Vision One Search App to hunt for malicious indicators.

-

processFilePath:*ProgramData\\session\\OriginLegacyCLI.exe AND objectCmd:*Windows\\SysWOW64\\waitfor.exe\" \"Event19030000000\" AND tags: "XSAE.F8404"

-

IOC

- Domains:

www[.]militarytc[.]com:443

Original link: https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/25/b/earth-preta-mixes-legitimate-and-malicious-components-to-sidestep-detection.html

Invisible obfuscation technique used in PAC attack

Summary

This article discusses a new JavaScript obfuscation technique used in a phishing attack targeting a major American political action committee (PAC) in early January 2025. The technique, which involves using Unicode filler characters (Hangul half-width and full-width) to represent binary values, was adopted rapidly after being publicly demonstrated by a security researcher. The attack utilized this invisible JavaScript, embedding it within another script as a base64-encoded string. The phishing attacks were highly personalized and employed anti-analysis techniques, such as debugger breakpoint timing evasion and nested Postmark tracking links, to obscure the final destination.

Technical Details

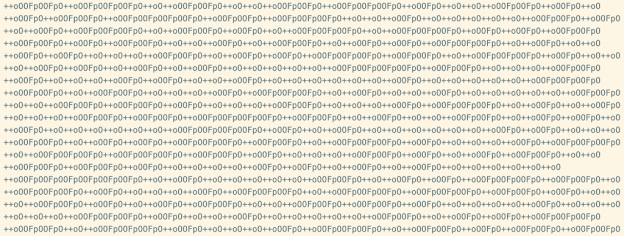

- Invisible JavaScript Obfuscation: The core technique uses two Unicode filler characters, Hangul half-width (\uFFA0) and Hangul full-width (\u3164), to represent the binary values 0 and 1, respectively. Each group of 8 of these characters forms a single byte, representing an ASCII character. The entire payload sits invisibly in a script as a property and is executed via a Proxy get() trap.

- Encoding Process: The encoding method was first demonstrated by Martin Kleppe on X and refined in a later post. The attack script contains a sequence of invisible Hangul filler characters within the whitespace.

- Base64 Encoding: The invisible JavaScript was further embedded in another script as a base64-encoded string.

- Anti-Analysis Techniques:

- The initial JavaScript attempts to invoke a debugger breakpoint and detects delays, aborting the attack by redirecting to a benign website if analysis is detected.

- Debugger breakpoint timing evasion is achieved by using

performance.now()to measure the time elapsed during debugger execution. If the time exceeds a threshold, the script redirects to a benign site. - The initial phishing links are wrapped recursively in Postmark tracking links, obscuring the final destination.

- Unraveling Postmark Links: The nested Postmark tracking links can be unraveled using a Python script that recursively extracts the URL-encoded target. The script uses regular expressions to match the Postmark link pattern and the

urllib.parse.unquotefunction to decode the URL. - Decoding Invisible JavaScript: A Python function is provided to decode the Unicode string of Hangul filler characters back to visible JavaScript code. The function reads the Unicode string, converts each 8-character sequence to a byte value, and then converts the list of bytes to a string.

Countries

- United States (Targeting affiliates of a major American political action committee)

Industries

- Political organizations

Recommendations

- Implement detection mechanisms for JavaScript obfuscation techniques, including the use of Unicode filler characters.

- Monitor for unusual patterns in base64-encoded strings within scripts.

- Analyze and unravel nested tracking links to reveal the final destination.

- Develop methods to detect and evade anti-analysis techniques like debugger breakpoint timing evasion.

- Utilize the provided Python code snippets to decode invisible JavaScript and unravel Postmark tracking links.

Hunting methods

- Inspect JavaScript code for Hangul filler characters (\uFFA0 and \u3164) used for obfuscation.

- Monitor network traffic for nested Postmark tracking links.

- Analyze scripts for debugger breakpoint and timing evasion techniques.

IOC

- Domains:

veracidep[.]ru

mentespic[.]ru

Original link: https://blogs.juniper.net/en-us/threat-research/invisible-obfuscation-technique-used-in-pac-attack

whoAMI: A cloud image name confusion attack | Datadog Security Labs

Summary

This article describes a name confusion attack where malicious actors can gain code execution within vulnerable AWS accounts by publishing AMIs (Amazon Machine Images) with specially crafted names. This attack exploits a pattern in how software projects retrieve AMIs to create EC2 instances. The vulnerability arises when the owners attribute is omitted during the AMI search, allowing attackers to insert malicious AMIs into the search results. If executed at scale, this attack could potentially compromise thousands of accounts, including internal non-production AWS systems. AWS has since introduced Allowed AMIs, which allows users to create an allow list of trusted AMI providers to mitigate this threat. Datadog has also released the whoAMI-scanner tool to detect the use of untrusted AMIs in an environment.

Technical Details

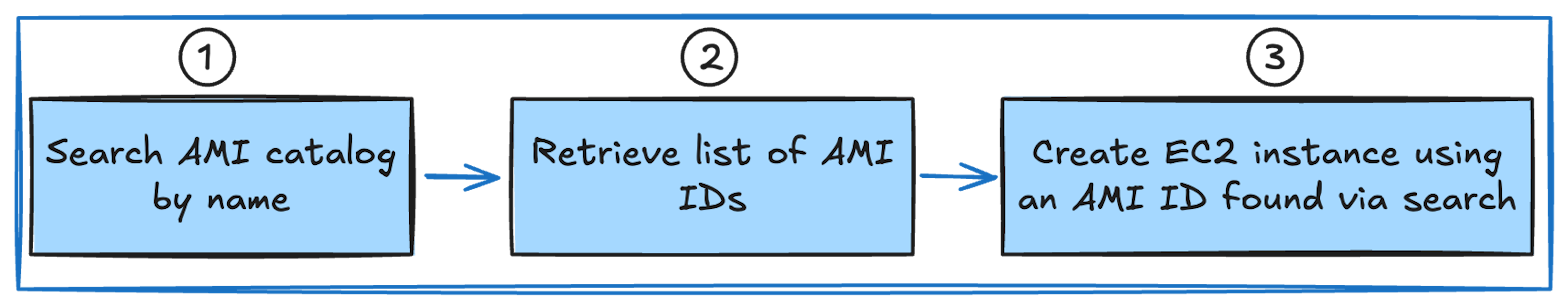

- Vulnerable Pattern: The attack targets the process of searching for AMIs by name without specifying the

ownersattribute. Specifically, theec2:DescribeImagesAPI call is exploited when it:- Uses the

namefilter. - Fails to specify the

owner,owner-alias, orowner-idparameters. - Retrieves the most recent image from the returned list.

- Uses the

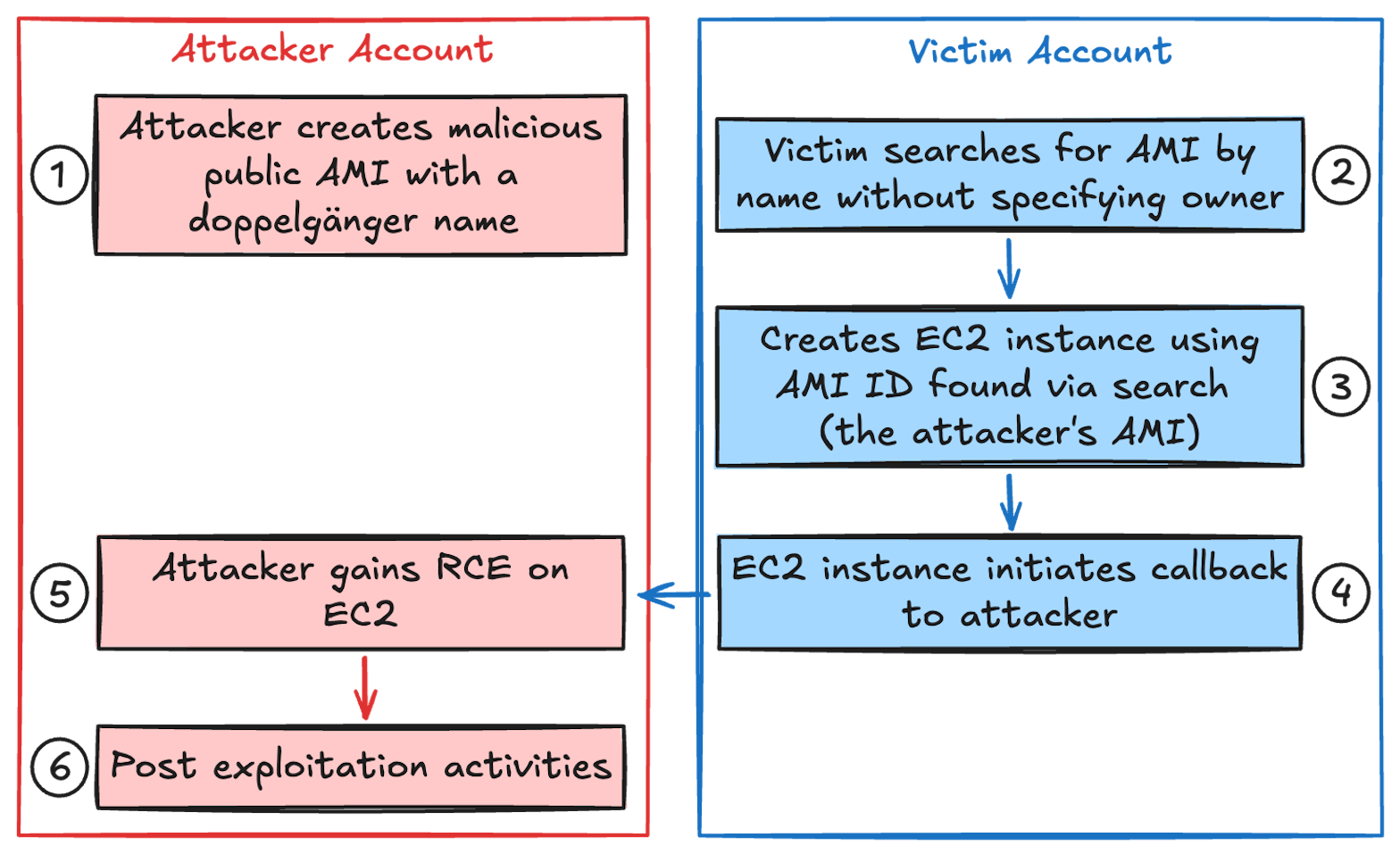

- Attack Execution:

- Attacker creates a malicious public AMI with a name that matches the search pattern used by the victim.

- Victim searches for an AMI by name without specifying the owner.

- Victim creates an EC2 instance using the AMI ID found via the search, which is the attacker’s malicious AMI.

- The EC2 instance initiates a callback to the attacker, granting the attacker Remote Code Execution (RCE).

- Exploitation Example: An attacker can publish a malicious AMI with a name like

ubuntu/images/hvm-ssd/ubuntu-focal-20.04-amd64-server-whoAMIto exploit a wildcard expansion pattern. - Affected Code: The vulnerability isn’t limited to Terraform but extends to other IaC tools, the AWS CLI, and various programming languages like Python, Go, and Java.

- AWS Vulnerability: Even internal non-production AWS systems were found vulnerable. Publishing AMIs with the prefix

amzn2-ami-hvm-2.0allowed arbitrary code execution within these AWS systems. - Mitigation: AWS introduced Allowed AMIs, which allows defining an allow list of trusted image providers by specifying account IDs or using keywords like “amazon” and “amazon-marketplace”.

- Detection Tools: Datadog created the whoAMI-scanner, a tool to audit running EC2 instances and identify those launched from public AMIs from unverified accounts.

Recommendations

- Use the

--ownersattribute when searching the AMI catalog to ensure only trusted AMIs are returned. Accepted values includeself,AN_ACCOUNT_ID,amazon, andaws-marketplace. - Enable and configure Allowed AMIs to create an allow list of trusted AMI providers.

- Regularly audit your AWS environment using tools like whoAMI-scanner to identify instances running AMIs from unverified accounts.

- Implement code analysis tools like Semgrep to detect vulnerable patterns in your code.

- Monitor the

ec2:DescribeImagesendpoint for queries without owner identifiers, followed byec2:RunInstancescalls. - Update Terraform AWS Provider: Ensure you’re using version 5.77 or later, which provides warnings when using

most_recent=truewithout filtering by image owner, and plan to upgrade to version 6.0 when it’s released, as it will make this an error.

Hunting methods

- Code Search (GitHub): Search your GitHub organization for the anti-pattern using queries that look for

aws_amidata sources withmost_recent = truebut withoutownersattributes. - Semgrep: Use the provided Semgrep rule to search your Terraform code for missing

ownersattributes inaws_amidata sources. - Datadog Cloud SIEM: Use the Cloud SIEM rule to detect

ec2:DescribeImagesqueries without owner identifiers followed byec2:RunInstancescalls.

Original link: https://securitylabs.datadoghq.com/articles/whoami-a-cloud-image-name-confusion-attack/